![]()

|

||||||||

| PEOPLE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Is it still meaningful to paint the human figure today—above all, the portrait?

For Fabrizio Ruggiero this question is not theoretical. It originates in a formative encounter, as a young visitor to the National Museum of Naples, standing before the frescoes of Pompeii. What struck him was not their subjects, but their surfaces: opaque, mineral, reticent. These walls did not offer stories; they absorbed the gaze. Colour, sand, terracotta and fragments of glass embedded in lime mortar drew the eye inward, toward a silence that precedes interpretation.

|

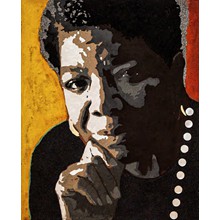

Maya Angelou |

||

From this experience Ruggiero understood that fresco does not simply represent the world—it resists translation into language. Its meaning is not stated but held, irreducible to words without being transformed into something else. Fresco, for him, becomes a language system: a grammar in which sense emerges through internal relations. Syntax, procedure and material structure replace narrative. Perception becomes an act of reading, a grammar of seeing.

|

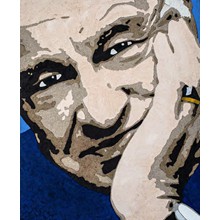

Edgar Morin Edgar Morin |

||

Working with sand, lime and mineral pigments—the elemental components of fresco—Ruggiero questions both the nature of colour and the contemporary status of painting. These materials are not historical residues but operative tools, reactivated through present technologies. His practice unfolds along multiple paths, all rooted in this ancient medium.

|

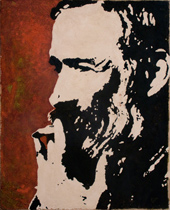

Constantin Brancusi |

||

| One of these paths is the close-up portrait, or, as he prefers, the Effigy— a term that better conveys the symbolic dimension of the image..

In Minimal Fresco, mortar and sand cease to be neutral grounds and become colour and texture themselves.

In Materic Fresco, thick layers of pre-pigmented plaster are applied with a palette knife, so that the construction of the image becomes inseparable from its subject.

The act of building is no longer a means to an end: it is the theme.

|

|||

|

|||

Enlarged to monumental scale, the portrait introduces a decisive condition: it can never be apprehended in its entirety. It is assembled fragment by fragment, recalling the Renaissance practice of cartoons and spolvero. Method prevails over likeness. The system that generates the image becomes primary, while the face, though still recognisable, recedes into a field of relations. Ruggiero ultimately conceives the human face as a territory, and painting as its cartography. Distinction, relation, pattern—these are the operations through which knowledge is constructed. Yet the map is never the territory. The description is not the described. The name is not the thing. In fresco, this distance is not a failure, but the very space in which meaning quietly comes into being. . |

Rabindranath Tagore |

||

|

|

|||